Hebrew Vowels

Introduction to the Nikkud

You will recall from your early school days that the English alphabet includes the vowel letters "A-E-I-O-U" (and sometimes "Y"). Unlike English, however, the Hebrew alphabet is a consonantal one: there are no separate letters for vowels in the written alphabet (though some letters, in particular Vav and Yod, can function as "consonantal vowels"). This does not mean, of course, that vowels are not used in Hebrew. In fact, it is impossible to say anything at all without vowel sounds. But ancient Hebrew contained no written vowels as distinct letter forms: the actual vowel sounds were "added" to the reading by means of oral tradition and long-established usage.

As an experiment, try reading the following:

Lv th Lrd yr Gd wth ll yr hrt

If you were able to "figure out" that the above string of letters reads

"Love the Lord your God with all your heart,"

(Deuteronomy 6:5),

then you might be able to see how a language could be entirely made

up of consonants—with the reader supplying the missing vowels.

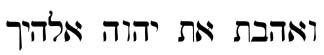

In written Hebrew the string of letters might look like this:

All of the letters in this string are Hebrew consonants - there is not a vowel in the bunch! In order to properly read this text, you, the reader, must supply the missing "1intonations" or vowels.

1 The rise and fall in pitch of the voice in speech.

Adding vowel sounds to a string of letters was not too difficult as long as you were immersed in the oral tradition and regular usage of the day. However, after the Diaspora more and more Jewish people began speaking the languages of their surrounding cultures —and literacy of the written Hebrew text became a more serious issue.

Sometime beginning around 600 A.D., a group of scribes in Tiberias called the Masoretes (mesora means "tradition") began developing a system of vowel marks (called neqqudot) to indicate how the text was traditionally read. Since these scribes did not want to alter the consonantal text, they placed these markings under, to the left, and above the Hebrew letters. Beside these vowel marks, the scribes also added "cantillation" marks (in Hebrew, ta'amim) to indicate how the text was to be chanted or sung.

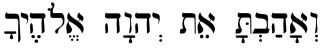

The "pointed" text of the Deuteronomy passage would now look like this:

Notice that the little marks - the dots and dashes and so on - appear mostly below the Hebrew letters. When you look (read) the Hebrew Scriptures or the prayerbook (Siddur), some of the script will begin to make sense.

The Hebrew alphabet contains 22 letters, while the English alphabet contains 26 letters and five of the letters are vowels; a, e, i, o, u and sometimes y. Ancient Hebrew contained no written vowels as distinct letter forms; the actual vowel sounds were “added” to the reading by means of oral tradition and long established usage.

Acrostics

When we read Esther 5:4 almost exactly in the middle of the book, it can be considered its pivotal verse: "So Esther answered, ‘If it pleases the king, let the king and Haman come today to the banquet that I have prepared for him.'" At this point Esther has committed herself in faith to her plan of action, and as yet she does not know if the king will intervene. It is in this context, then, that God's name "appears."

In Hebrew the phrase "let the king and Haman come today" is four words: Yaabow' Hamelek Wahaamaan Hayown. The initial letters of this phrase forms an acrostic, Y-H-W-H, the consonants that spell the name Yahweh, translated LORD in the Scriptures.

Acrostics, especially those that spell out God's name, are very rare. In fact, Jewish copyists carefully guarded against the accidental 1acrostic that might spell out this divine name because it was considered 2inviolate and 3ineffable. We can only assume, then, that this acrostic is purposeful, including God in the events of Esther's day, though working in the background.

1 A number of lines of writing, such as a poem (or verse), certain letters of which form a word, proverb, etc. A single acrostic is formed by the initial letters of the lines, a double acrostic by the initial and final letters, and a triple acrostic by the initial, middle, and final letters

2 Free from violation, injury, desecration, or outrage.

3 Incapable of being expressed; indescribable or unutterable.